Flor Cadáver

Francisco Trêpa

[04/04/24 - 12/05/24]

Foco Gallery is pleased to present Flor Cadáver, a solo show by Francisco Trêpa.

Curated by Ana Cristina Cachola

A FLOWER, FOR LOVE

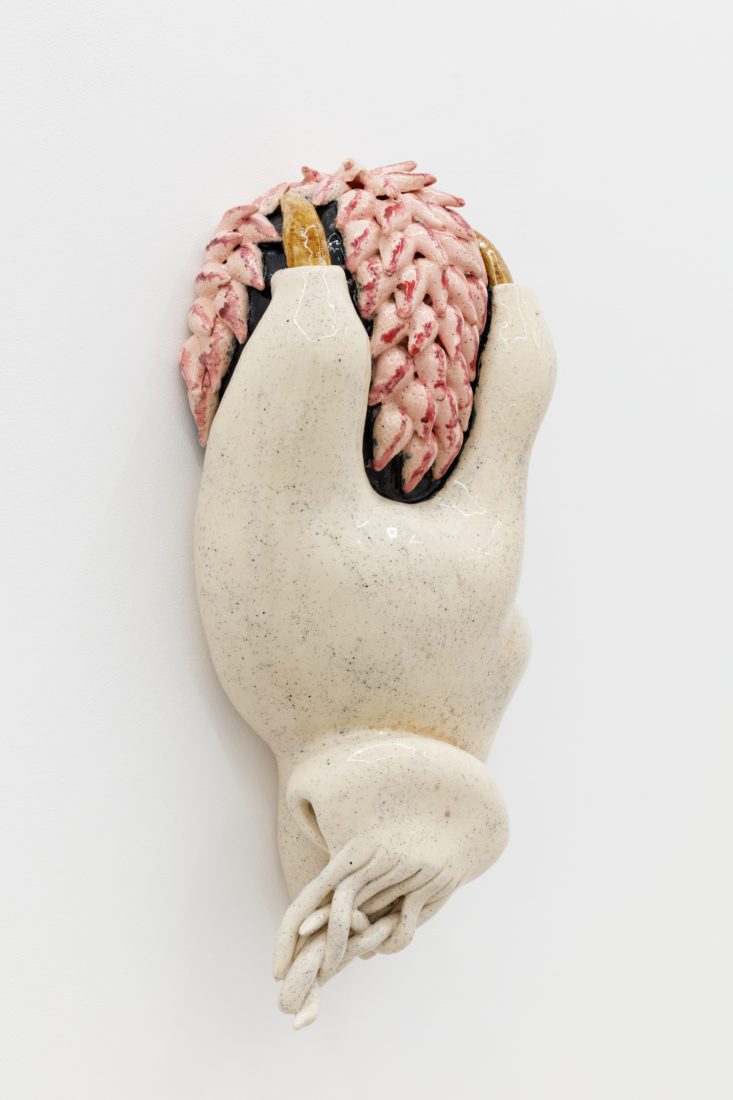

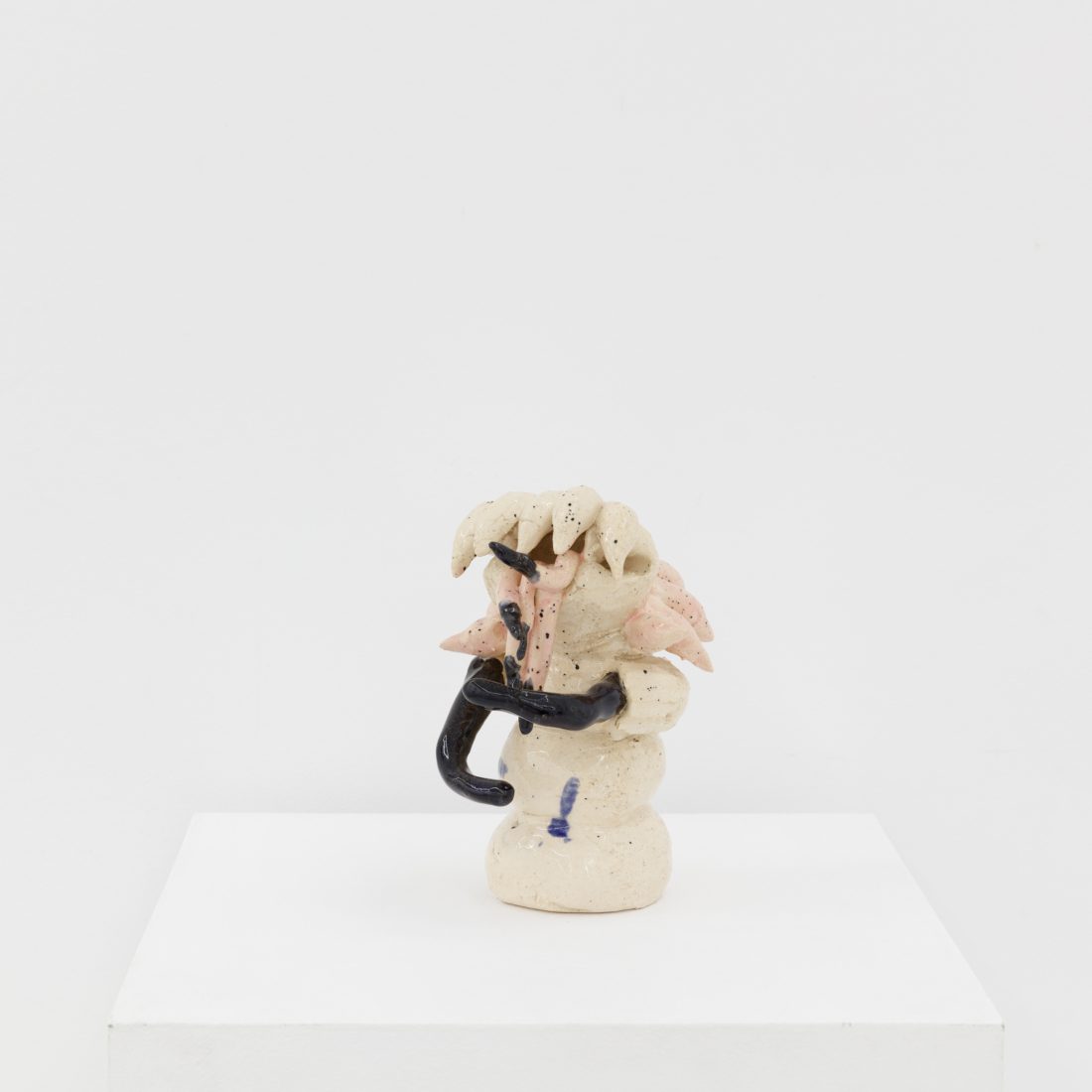

When the eye lands upon a virtuous ceramic work by Francisco Trêpa, we promptly believe it does not belong to this world; yet, we have no doubts that it belongs to another – it contains an ontology of belonging that intrigues us like a kind of magnetic field. Therefore, we cannot stop looking at it, we let it seduce us and then we want to follow it, to know where it comes from. In “Flor-Cadáver,” Trêpa’s first solo exhibition at the Gallery, this magnetic field will lead us to encounter deep affections, inquiries, and autofictions.

In a more extensive exploration of pollinators and their importance in the survival of planetary life, Francisco Trêpa discovers the Rafflesia: it is a genus of leafless parasitic plant, known for producing the world’s largest flower. The Rafflesia is native to Southeast Asia, especially Indonesia, and its flower emits a strong and unpleasant odor, similar to that of a decomposing body, which attracts pollinating insects like flies and beetles. In other words, it often pretends to be dead. This pretense of the titular protagonist, which punctuates various moments of the exhibition, spreads throughout the rest of the scenery. Trêpa’s multitude of pollinators are arranged in specific narratives, more or less dramatic (feigned?). They are all there in this exhibition universe to remind us of their existence and appeal for survival.

Pollinators occupy a place of crucial importance in the survival of the human species and planet Earth. Due to habitat loss, pesticide use, climate change, diseases, and parasites, many are on the brink of extinction, with all that entails. It is no different in Trêpa’s pollinator universe, where both the keeper and the killer emerge – the ambiguity of the human being as guardian or murderer of these creatures. Trêpa’s hands, gestures, and body can inform us but also shape us (we will certainly become more attentive). Drones are added to the pollinators, which replace them in turn. The drone insinuates itself, however, in a less direct manner, through inscriptions, decorations, and repetitions of minimal objects. The scenes we witness ensure the narrative axis of the exhibition, but they do not unveil all the narratives. We will not know the future of these beings.

In Francisco Trêpa’s works, there is always a dynamic relationship with matter (and the materials he uses), and in several cases, the plastic and imagetic suggestions do not serve as a substitution for the material world, not being a sign for something else, but rather they hold the power to create “tropes” of new universes and their imaginaries. Trêpa’s work thus summons various “tropes” — nature, landscape, plants, flowers, dreams, the oneiric, the possibilities of figuration, the (de)construction of places, the unpredictability of matter, just to mention a few —, which are placed in a state of suspension, seeming that each of his pieces is in a constant metamorphic and performative condition, so that, even when materially static, they show themselves endowed with consequent movement. In this sense, Trêpa’s artistic practice lacks a monolithic and crystallized ontology, because, despite the constancy, there are multiple reverberations and suggestions in the viewer’s gaze.

The artist identifies the respective field of research as baroque sci-fi, a lineage that articulates elements of this ornamented aesthetic with themes and concepts from science fiction. In “Flor-Cadáver,” the complexity of reality and the collapse of binary thought are explored, the fusion between the organic and the technological (very evident in the case of pollinating drones). Complex narratives, visually rich and full of symbolic charge, compose Trêpa’s working matrix: love, gesture, and thought. This exhibition has no end, it has only one destination: the embrace, the universal need for connection and empathy, transcending differences in species or origin.

April 2024,

Ana Cristina Cachola