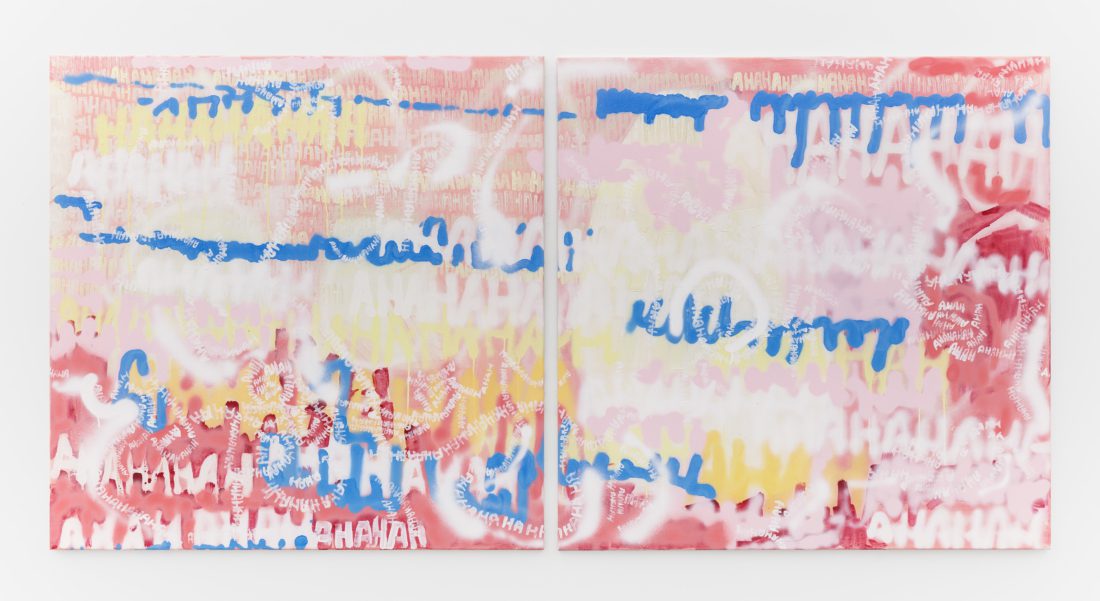

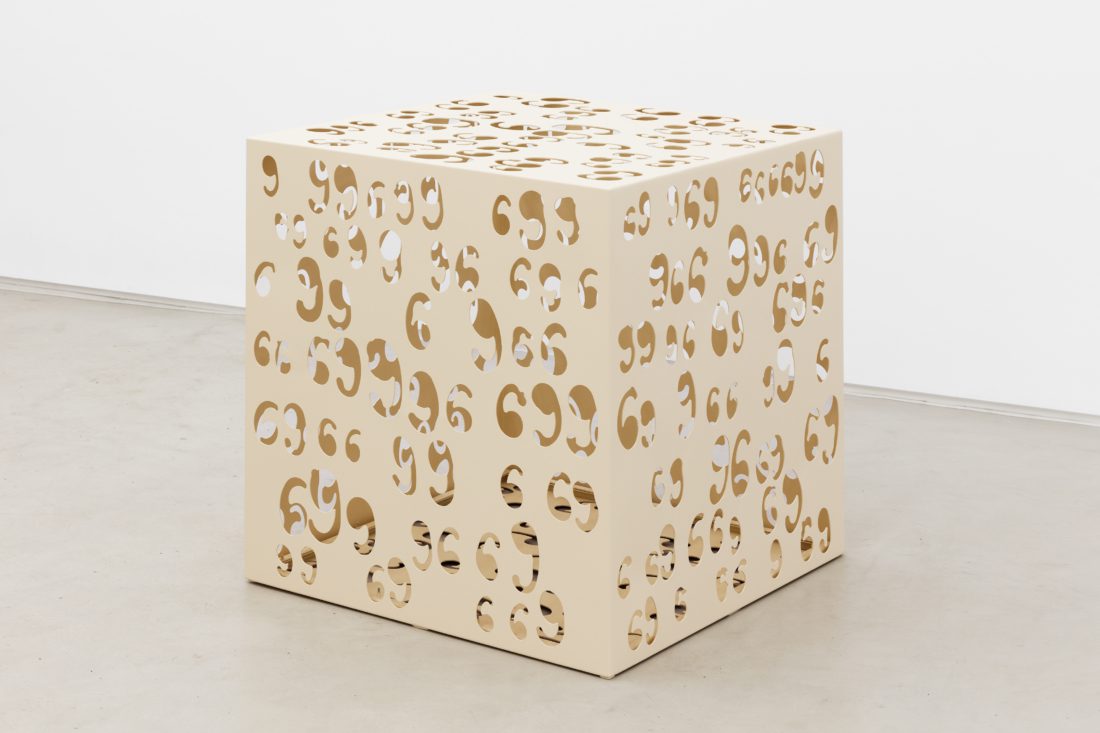

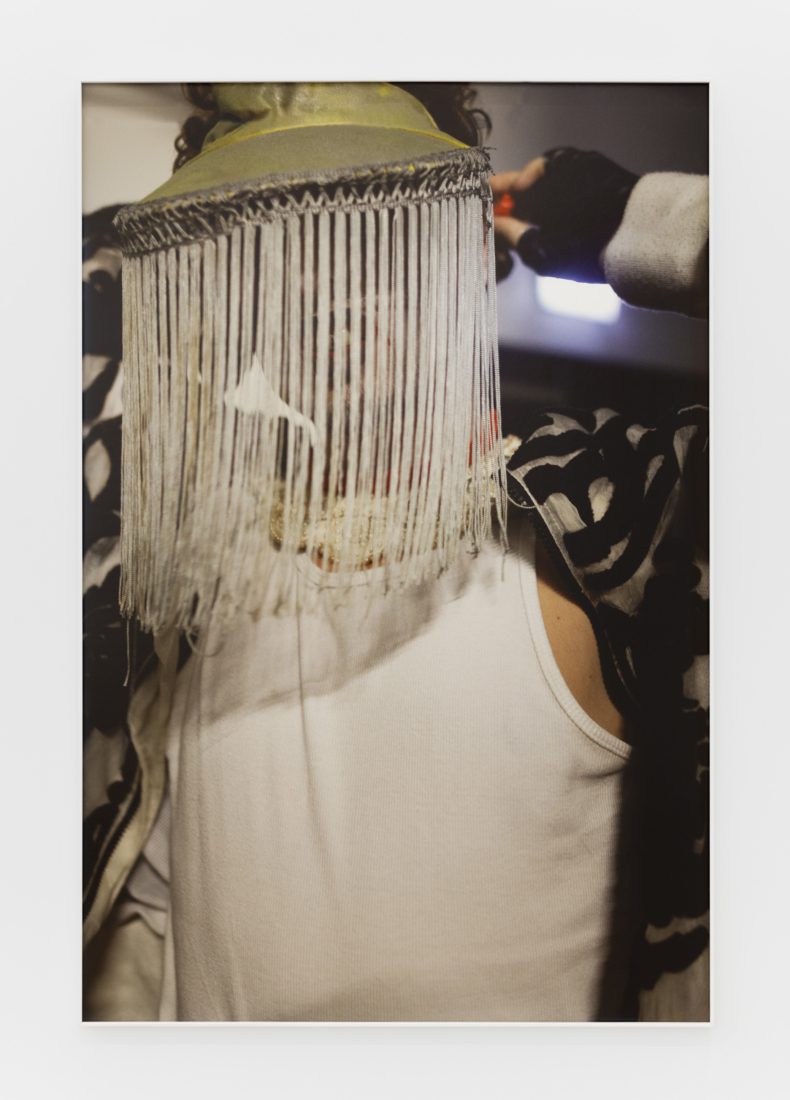

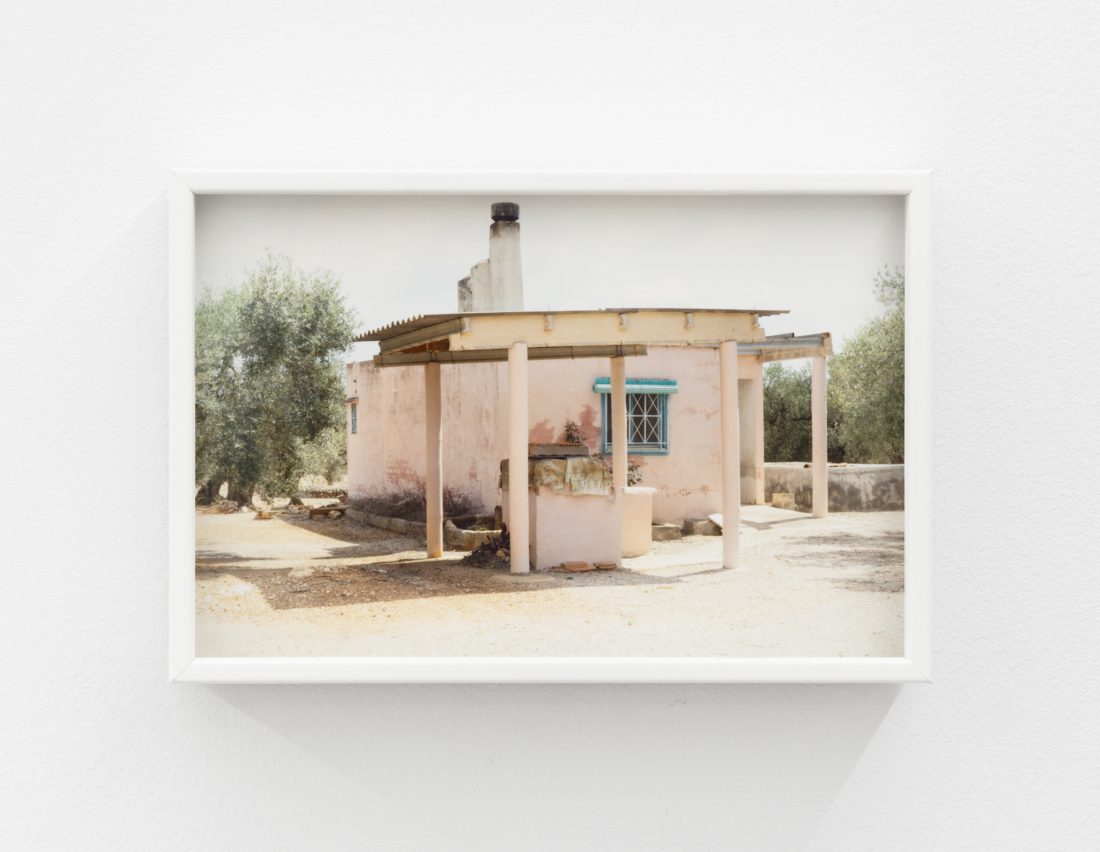

Unconscious Fruit

Francisco Osório

[15/09/22 - 22/10/22]

In the blue morning light of a forgotten Thursday, Oscar Wilde leaves his residence to go for a walk around a public garden. No one is there yet, it’s even too early for the birds. He was awoken suddenly and couldn’t remember what stories had come to him in night. They would, later, reappear in the “Picture of Dorian Gray”.

On a dull and rainy, lonely New York evening, Susan Sontag, having finished the last of the “Rolling Stone Interviews”, also goes for a walk. She is full of having listened to other peoples confessions. That night she sleeps and dreams Jim Morrison’s dreams. She wakes up and continues to write other theories about other people who take photographs.

Before climbing the Himalayas, Sir. Edmund Hillary dreams of himself summating the highest peak. In that premonition, he is alone with his equipment and his ambition. What would come to pass would include the guardian, Tenzin Norgay, who helped him reach that height. This un-sung sherpa had not appeared to him the night before.

_

What you have just read are fictitious accounts, and maybe also true as metaphors. They are dreams conjured in waking life, of other lives which have passed before this one. And they testify to the introductory fine line between imagination and dreams which may be divided only by the distinction between “awake” and “asleep”.

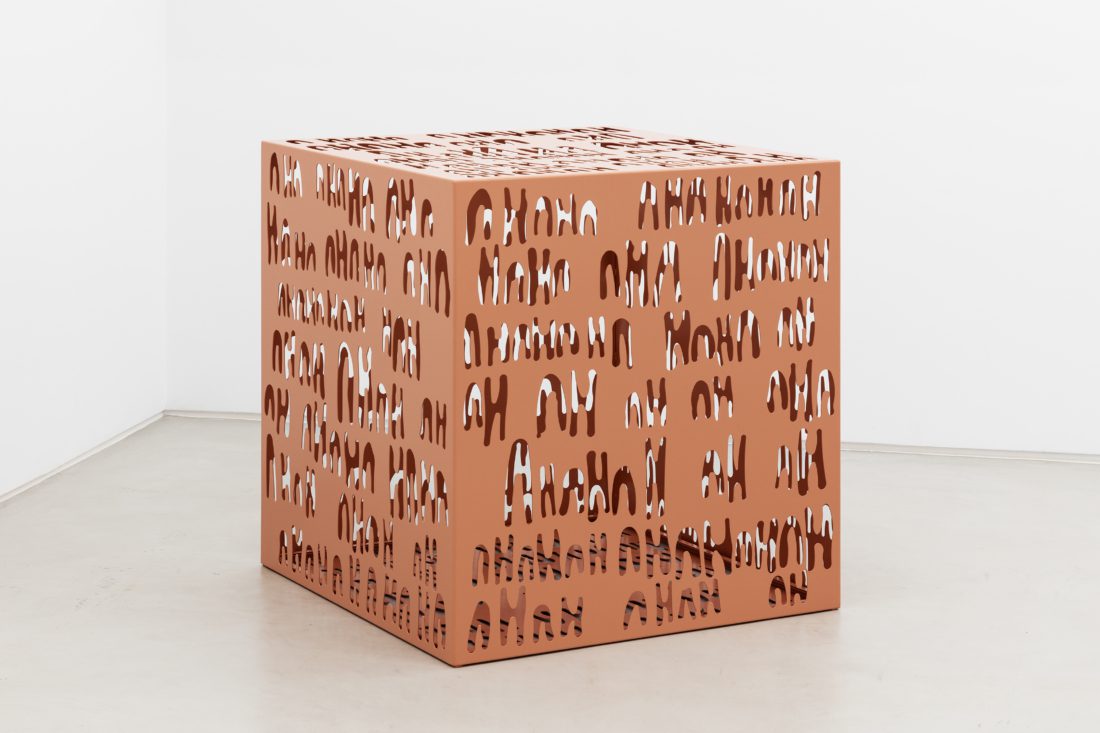

The subject of this exhibition, “Unconscious Fruit” is the inner life of the artist, Francisco Osório. In early talks, he spoke of his dreams as charged and prolific. Much of what is figured in these paintings, photographs, sculptures, and videos come for this hidden place, from the place of allegory and truth when one sleeps. Dreams are contagious. The day after I was asked to curate this exhibition, I began dreaming and each night that has followed I dream with more intensity, in Kodachrome. Dreams are like an invisible medicine that one takes without knowing one needs it. They are also a cleaning of the system. They are also cultural. They are also possibly the most personal kind of event next to secrets.

In 2019, before Covid, a society of American anthropologists met for an inaugural conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico to discuss and advocate for a new anthropology of dreaming. The argument being that this noble social science has dedicated its work to waking life and thus has neglected a huge part of the human experience, sleeping life. They faced, and still face, the huge challenge of recollection itself, of the art of memory and its subjectivity which can be debated yet cannot be quantified. In certain, non-occidental cosmologies, the dream space acts as a portal for communications with ancestors. Yet, we must ask the question, does an analysis of dreaming also implicate a content of dreaming which is prejudiced to favour socio- economic, historical, and cultural sanctions? The tendency for these factors to infiltrate all areas of life is strong. So, is the dream a pure space? A space free of these oppressions? Could it be so? Or is the dreamscape also a corrupted space? In either case, validating sleeping life, as also life and living, is hugely important. So, “do androids dream of electric sheep”?

Is it rare to have the opportunity to work closely with an artist who is concerned with the symbol and the sign such as Francisco Osório. This, as the core of Osório’s research both as an artist and human being, positions him to generate a hermeneutics encapsulated in his artistic output. The grandfather of anti-Freudian dream theory movements is Carl Jung. In his seminars on dreams, he details a number of accounts of his patients and then taps certain archetypes which he maps onto their dreams, ever concerned not to label anything purely libidinal. In Jung’s diaries, he detailed extensively of own dreams and the synchronicities that appeared with events in waking life and the dreams of his patients. For Jung, whatever is rejected from the self appears in the world as an event. In pairing these two figures, Osório and Jung, there are many distinctions, but what is of particular interest here is that Osório does not busy himself with hierarchising mystery. He channels and that truly unique in the context of a visual arts exhibitionary complex that is obsessed with the denial of intuition as method and the reiteration of the educational turn which prizes discursive justification over the emotional body of the artist. So, what do Oscar Wilde, Susan Sontag, Sir Edmund Hillary, Tenzin Norgay, Carl Jung, Francisco Osório, and every person who sees this exhibition have in common? The utter and complete potency of their unconsciouses, the dream as a mediating fluid territory, and the presence of mind to care about art and the world.

“Unconscious Fruit” can be eaten, it is juicy and abundant. It arises from the part of the mind which is a screen for the heart and its desires. Sitting at the table, one finds that this kind of fruit is sweet and sour at the same time.

-Josseline Black September, 2022

Photography © Photodocumenta