I am Curious Blue

Rui Palma + Kuril Chto

[06/07/23 - 25/07/23]

I am Curious Blue

It is nearly impossible to divorce the history of the body from the history of sexuality. There is no clear analytical method escaping the difficulties with this genealogy, considering that the body is alive and history is dead. Art exercises its right to visualise and map this genealogy onto the present and future.

When we think about sex, we face our habituated notions of desire which embed themselves in the Post-Fordist regime of late neoliberal capitalism. Arguably, some future which offers a safe and loving environment for the body, means the enactment of a massively different quality of collective libido. Mark Fisher’s final lectures offer us this notion as a necessity. The question is posed: what is a libido which doesn’t need immediate fulfilment? From where does it emerge, and if it emerges can it rewrite the laws of the economic systems which govern the planet?

Understanding Jean Baudrillard’s position that: “the whole, obsessed as it is with maximising power and sex, must be questioned as to its emptiness. Given its obsession with power as continuous expansion and investment, one must ask it the question of the reversion of the space of power, and of the reversion of the space of sex and its speech. Given its fascination with production, one must as it the question of seduction.” Perhaps Baudrillard is affirmed that the dynamics between production and seduction are profound. He dedicates a treatise to this idea in 1979. For the purposes of analysis we have to categorise separately: power, seduction, sex, and libido. Returning now to this space in 2023, we see an exhibition which faces and opens the lines between these four concepts. Ultimately, it looks for for a ‘future libido’ or ‘post libido’ as a remedy as a solution for post-capitalist desire: Curiosity. I am Curious Blue.

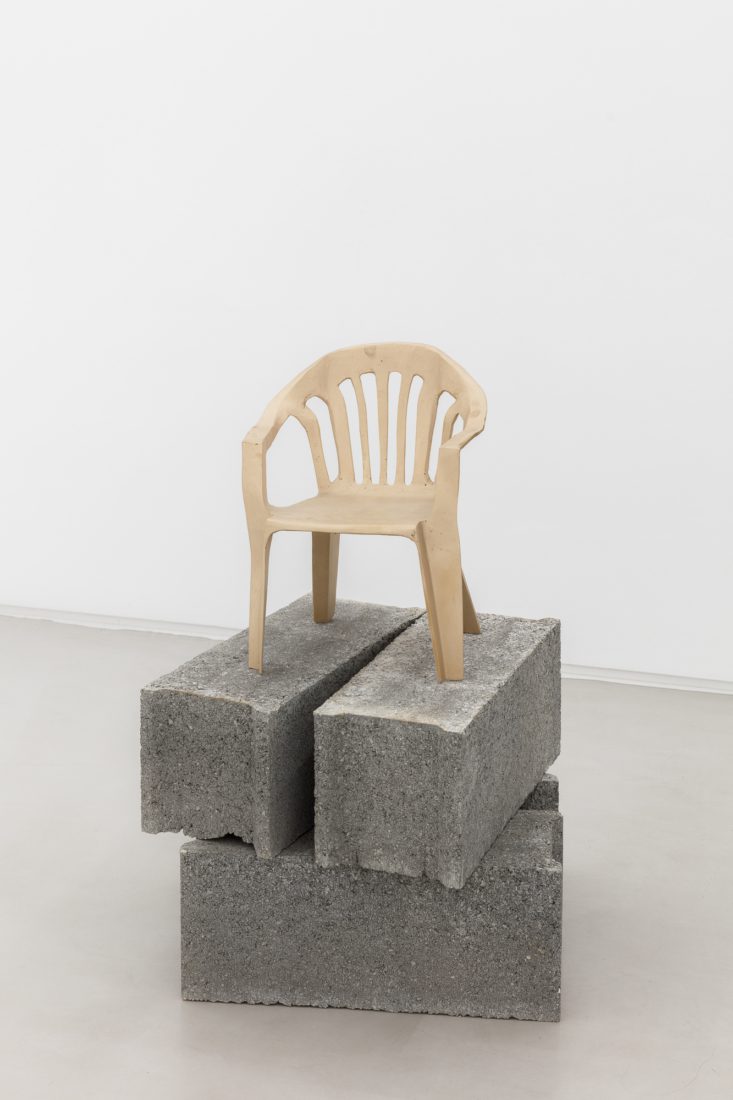

With Kuril Chto, we see objects as erotic while finding humour in the codes of objectification, some gentle and some pornographic, which make the body a territory for analysing the state of things. Meanwhile, we are asked to address the Mono Blanc (white plastic chair), as an archetype exemplifying the overlap between production (industrial) and reproduction (sexual). So too, everyone has a memory of this plastic chair. Chairs are pumped out on assembly lines, babies are conceived every 30 seconds. Plastic is recycled, lives are short.

And what of laughter? What of the small moments in this grand machine running on the excess of desire? Chto’s work, exercising its varied materiality says subliminally: play.

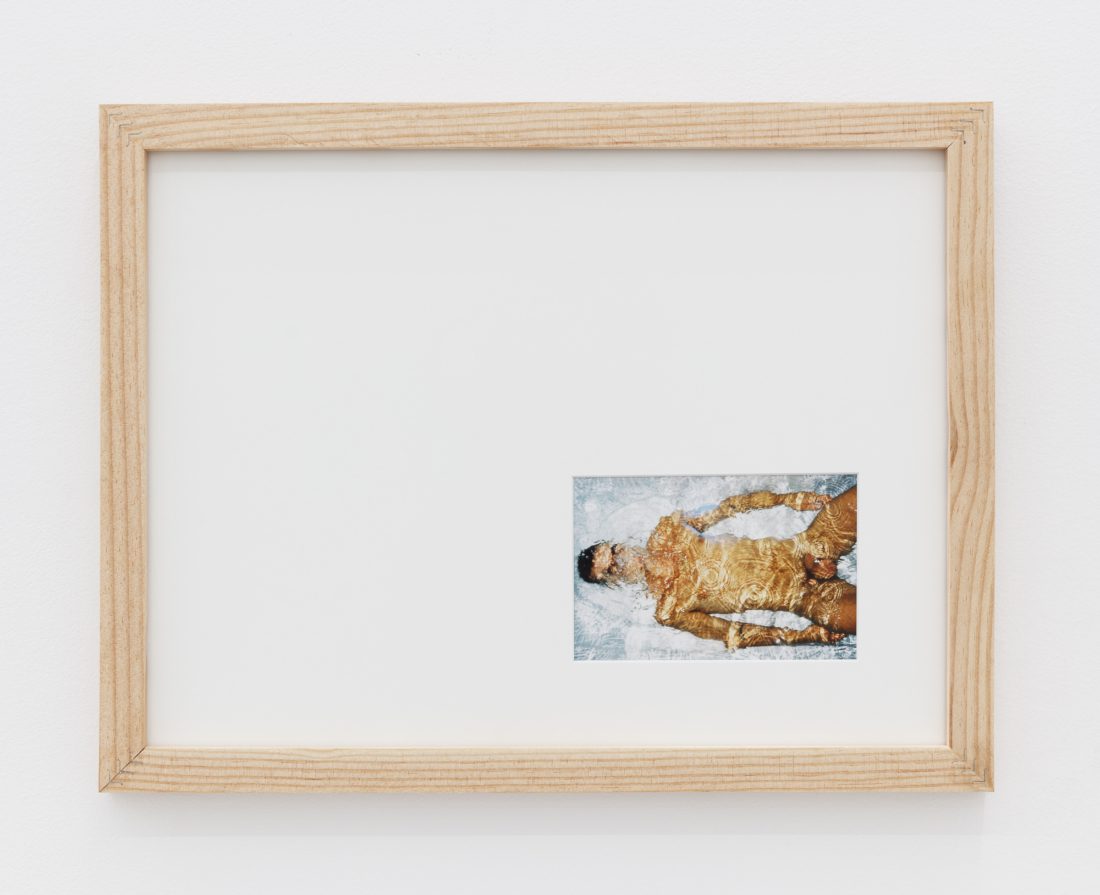

With Rui Palma, we see protagonists, human and non- human, who inhabit their environments with tender nervous systems open to change. Palma’s figures remind us of the Swami Rama Tirtha’s words:

See, today I am telling you the secret,

Hear my confession from my own lips.

Whether as a lover or a thief…

I am a storm to engulf

All laws, trials and cross-examinations for ever.

The whole world is just myself,

Snoring in ecstasy…

Catch me if you can.

“Whether as a lover or a thief…Catch me if you can”- this is Palma’s challenge to us. His photography and video are evident in themselves and not of themselves.

In being both abstract and figurative, there is a non- binary mysticism which emerges, as a kind of song of enlightenment. As an ode to change. His work is also a defence of magic, being deeply linked to the totemic. The reclamation of innocence which persists in Palma’s work, asks for a kind of revolution for touch and being touched by one’s own memory. The poetic, here, as emancipatory. The image as a chamber for the heart, simultaneously ecstatic and melancholic.

So, why blue? Blue, according to most color theory, enhances sensitivity. We live in a world violently saturated with representation. We also live in a world that requires a level of ‘killer instinct to survive, it forces the sweetness out of things. Palma and Chto want that sweetness back.

On another level, the title of the exhibition was taken from a 1968 Swedish film directed by Vilgot Sjöman, starring Lena Nyman. The film is critique of a system which prioritises religion over the freedom of sexual expression. Seized by customs upon entry to the United States, the film was the subject of a heated court battle. It was banned by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that labeled the film obscene—and therefore subject to state regulation. After 34 years, Criterion released it with a director’s interview. It remains in the public sphere.

What is interesting about this film and the dialogue between Kuril Chto and Rui Palma’s work is not the assumption of the transgressive possibility of art, but rather, the delicacy of the creative (to create, to birth, to bring into the world) act in the context of a system which overlooks things while taking advantage of them. There will always be oppression, and the question remains: will we cultivate new relationships to our bodies and our sexuality? Will we exercise our curiosity?

Will we stay ‘blue’?

-Josseline Black